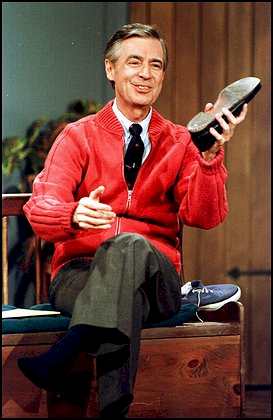

Highlights in the career of Fred Rogers The cause was stomach cancer, said David Newell, a family spokesman who also portrayed Mr. McFeely, of the Speedy Delivery Messenger Service, one of the regulars on "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood." Mr. Rogers entered the realm of children's television with a local show in Pittsburgh in 1954. But it was the daily half-hour "Neighborhood" show, which began nationally on public television in 1968 with homemade puppets and a cardboard castle, that caught on as a haven from the hyperactivity of most children's television. Let morphing monsters rampage elsewhere, or educational programs jump up and down for attention; "Mister Rogers" stayed the same year after year, a low-key affair without animation or special effects. Fred Rogers was its producer, host and chief puppeteer. He wrote the scripts and songs. Above all he supplied wisdom; and such was the need for it that he became the longest-running attraction on public television and an enduring influence on America's everyday life. For all its reassuring familiarity, "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" was a revolutionary idea at the outset and it remained a thing apart through all its decades on television. Others would also entertain the young or give them a leg up on their studies. But it was Fred Rogers, the composer, Protestant minister and student of behavior who ventured to deal head-on with the emotional life of children. "The world is not always a kind place," he said. "That's something all children learn for themselves, whether we want them to or not, but it's something they really need our help to understand." He believed that even the worst fears had to be "manageable and mentionable," one way or another, and because of this he did not shy away from topics like war, death, poverty and disability. In one classic episode he sat down at the kitchen table, looked straight into the camera and calmly began talking about divorce: "Did you ever know any grown-ups who got married and then later they got a divorce?" he asked. And then, after pausing to let that sink in: "Well, it is something people can talk about, and it's something important. I know a little boy and a little girl whose mother and father got divorced, and those children cried and cried. And you know why? Well, one reason was that they thought it was all their fault. But, of course, it wasn't their fault." When the Smithsonian Institution put one of Mr. Rogers's zippered sweaters on exhibit in 1984, no one who had grown up with American television would have needed an explanation. He had about two dozen of those cardigans. Many had been knitted by his mother. He wore one every day as part of the comforting ritual that opened the show: Mr. Rogers would come home to his living room — a set at WQED-TV in Pittsburgh — and change from a sports coat and loafers into sweater and sneakers as he sang the words of his theme, "It's a beaut-i-ful day in this neighborhood . . . won't you be my neighbor?" This would be followed by a talk about something that Mr. Rogers wanted people to consider — maybe the obligations of friendship, or the pleasures of music, or how to handle jealousy. Then would come a trip into the Neighborhood of Make-Believe, where an odd little repertory company of human actors and hand puppets like King Friday XIII and Daniel Striped Tiger might dramatize the day's theme with a skit or occasionally stage an opera. The show had guests, too, often musicians like Wynton Marsalis or Yo-Yo Ma, and field trips. Mr. Rogers would venture out to show what adults did for a living and the objects made in factories, passing along useful information along the way. Visiting a restaurant for a cheese, lettuce and tomato sandwich, he would stop to demonstrate the right way to set a table. And the sign that said restroom? It just meant bathroom, and most restaurants had them, "if you have to go." Among his dozens of awards for excellence and public service, he won four daytime Emmys as a writer or performer between 1979 and 1999, as well as the lifetime achievement award of the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences in 1997. Last year President George W. Bush gave him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. No visit to the Neighborhood was complete without the counsel and comfort to be found in his easy-to-follow songs, which covered everything from the beauty of nature to the common childhood fear of being sucked down the bathtub drain with the water. He wrote about 200 songs and repeated many of them so regularly that his viewers, most of them between 2 1/2 and 5 1/2 years old, knew them by heart. "What Do You Do," about controlling anger, began this way: What do you do with the mad that you feel When you feel so mad you could bite? When the whole wide world seems oh, so wrong And nothing you do seems very right? What do you do? Do you punch a bag? Do you pound some clay or some dough? Do you round up friends for a game of tag? Or see how fast you can go? It's great to be able to stop When you've planned a thing that's wrong. Long ago, in the days before grown-ups learned how say to "mission statement," Mr. Rogers wrote down the things he wanted to encourage in his audience. Self-esteem, self-control, imagination, creativity, curiosity, appreciation of diversity, cooperation, tolerance for waiting, and persistence. It was no coincidence that his list reflected the child-rearing principles gaining wide acceptance at the time; he worked closely with people like Margaret McFarland, a leading child psychologist, who was until her death in 1988 the principal adviser for "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood." Like any good storyteller, he believed in the power of make-believe to reveal truth, and he trusted children to sort out the obvious inconsistencies according to their own imaginations, as when the puppet X the Owl's cousin, for example, turned out to be the human Lady Aberlin in a bird suit. His flights of fantasy probably reached their apex in his extended comic operas; "trippy productions," as the television critic Joyce Millman called them, that were "a cross between the innocently disjointed imaginings of a preschooler and some avant-garde opus by John Adams." At least one of these works, "Spoon Mountain," was adapted for the stage. It was presented at the Vineyard Theater in New York in 1984. Those who knew Mr. Rogers best, including his wife, said he was exactly the same man on-camera and off. That man had a much more complex personality than the mild, deliberate, somewhat stooped fellow in the zippered sweater might let on. One got glimpses of this in film clips of him behind the scenes, especially when working his hand puppets: here he wore a black shirt to blend into the background, became lithe and intense, and changed his voice and attitude like lightning as he switched back and forth between characters. He was Henrietta Pussycat, who spoke mostly in meow-meows; the frequently clueless X the Owl; Queen Sara; the pompous and pedantic King Friday XIII; Lady Elaine Fairchilde, heavily rouged and evidently battle-tested in the theater of life; and others. He inhabited his characters so artfully that Josie Carey, the host of an earlier children's series in which Mr. Rogers did not appear on camera, said that she would find herself confiding in his puppets and completely forgetting he was behind them. He had known everything about puppets for a long time, since his solitary childhood in the 1930's. The story of how he and they came to appear together on television is a good one. Fred McFeely Rogers was born in Latrobe, Pa., on March 20, 1928, the son of Nancy Rogers and James H. Rogers, a brick manufacturer. An only child until his parents adopted a baby girl when he was 11, and sometimes on the chubby side, he spent many hours inventing adventures for his puppets and finding emotional release in playing the piano. He could, he said, "laugh or cry or be very angry through the ends of my fingers." He graduated from Latrobe High School, attended Dartmouth College for a year, and then transferred to Rollins College in Winter Park, Fla., graduating magna cum laude in 1951 with a music composition degree. From there he intended to study at a seminary. But his timetable changed in his senior year when he visited his parents at home and saw something new to him. It was television. Something "horrible" was on, he remembered — people throwing pies at one another. Still, he understood at once that television was something important for better or worse, and he decided on the spot to be part of it. "You've never even seen television!" was his parents' reaction. But right after graduating from Rollins he got work at the NBC studios in New York, first as a gofer and eventually as a floor director for shows like "The Kate Smith Evening Hour" and "Your Hit Parade." In 1953 he was invited to help with programming at WQED in Pittsburgh, which was just starting up as this country's first community-supported public television station. The next year he began producing and writing "The Children's Corner," the show with Ms. Carey, and he simply brought some puppets from home and put them on the air. In its seven-year run, the show won a Sylvania Award for the best locally produced children's program in the country, and NBC picked up and telecast 30 segments of it in 1955-56. Meanwhile, Mr. Rogers had not given up his other big goal. Studying part-time, he earned a divinity degree from the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary in 1962. The Presbyterian Church ordained him and charged him with a special mission: in effect, to keep on doing what he was doing on television. He first showed his own face as Mister Rogers in 1963 on a show called "Misterogers" when the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation asked him to start a show with himself as the on-camera host. The CBC-designed sets and other details became part of the permanent look of Rogers productions. But as for Canada, Mr. Rogers and his wife, Joanne, a pianist he had met while at Rollins, soon decided they should be raising their two young sons back in western Pennsylvania. Mr. Rogers returned to WQED where, in 1966, "Misterogers' Neighborhood" had its premiere in its fully developed form. It was distributed regionally in the East, and then, in 1968, what became PBS stations began showing it across the country. In their own way, the shows and Mr. Rogers's

production company, Family Communications, constituted one of the country's more stable

little industries. Underwriting by the The unlikelihood of such an institution, along with Mr. Rogers's mannerisms — that gleaming straight-ahead stare, for instance, which could be a little unnerving if you really thought about it — made parody inevitable. Perhaps the most famous sendup was on "Saturday Night Live," with Eddie Murphy as a black "Mr. Robinson" who lamented: "I hope I get to move into your neighborhood some day. The problem is that when I move in, y'all move away." When Mr. Murphy later met Mr. Rogers, it was reported, he did what most everyone else did. He gave him a hug. Mr. Rogers was a vegetarian and a dedicated lap swimmer. He did not smoke or drink. He never carried more than about 150 pounds on his six-foot frame, and his good health permitted him to continue taping shows. But two years ago he decided to leave the daily grind. "I really respect opera singers who stop when they feel that they're doing their best work," he said at the time, expressing relief. The last episode was taped in December 2000 and was shown in August 2001, though roughly 300 of the 1,700 shows that Mr. Rogers made will continue to be shown. He took a few years off from production in the late 1970's, and later, toward the end of his long career, he cut back to taping 12 or 15 episodes a year. Although his show ran daily throughout those years, what his latter-day viewers saw was a mix of new material and reruns, the differences between them softened by a bit of black dye in Mr. Rogers's gray hair. As a spokesman for Mr. Rogers said, it didn't matter so much that the shows were repeated: the audience was always new. Mr. Rogers kept a busy schedule outside the Neighborhood. He was the chairman of a White House forum on child development and the mass media in 1968, and from then on was frequently consulted as an expert or witness on such issues. He produced several specials for live television and videotape. Many of his regular show's themes and songs were worked into audiotapes. There were more than a dozen books, with titles like "You Are Special" and "How Families Grow.' He was also one of the country's most sought-after commencement speakers, and if college seniors were not always bowled over by his pronouncements, they often cried tears of joy just to see him, an old friend of their childhood. When he was inducted into the Television Hall of Fame in 1999, he began his formal acceptance speech by saying, "Fame is a four-letter word." And now that he had gotten the attention of a house full of the industry's most powerful and glamorous names, he asked them to think about their responsibilities as people "chosen to help meet the deeper needs of those who watch and listen, day and night." He instructed them to be silent for 10 seconds and think about someone who had had a good influence on them. Mr. Rogers's Web site, www.misterrogers.org, provided a link to help parents discuss his death with their children. "Children have always known Mister Rogers as their `television friend,' and that relationship doesn't change with his death," the site says. "Remember," it added, "that Fred

Rogers has always helped children know that feelings are natural and normal, and that

happy times and sad times are part of everyone's life."  In July, 2002, President George W. Bush presented the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Fred Rogers in a ceremony in the East Room of the White House

Yes, Fred Rogers really was like that. There was no act, no contrivance. In the truest sense of the word, he never performed. How, or why, would you fake that? The mildest of TV stars, he was also among the most fearless and honest. Fred Rogers, who died Thursday, February 27, 2003, at the age of 74, changed little about "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" from the moment it went on the air in 1966 until his last show in 2001. He unapologetically produced a program with almost no production pizazz and certainly no concession to adult sensibility. He spoke directly to children, without irony or sarcasm or the giddiness that has infected "children's programming" from Disney's "Steamboat Willie" to "Teletubbies." The program was like a prayer -- peaceful, deliberate, rhythmic, insulated from noisy concern. Every weekday for a half-hour, through almost 900 episodes, it was pretty much the same. And that was the point. Rogers -- learned in child development, an ordained Presbyterian minister -- knew that children are comforted by ritual, reassured by the redundant. Mister Rogers' television neighborhood was about a whole bunch of insignificant things -- could anyone follow the loopy story lines unfolding in the Neighborhood of Make Believe? -- and a few gigantic things: respecting yourself and others, using your imagination, understanding your feelings. So much is iconic now. The dorky wingtips giving way to the unbeautiful sneakers. The zippered cardigan, taken from the closet and wrapped around the slightly sunken chest. The skinny necktie. The fish food. The reassuring and somewhat wussy voice. That voice! Mister Rogers was the most easily mimicked man on TV, maybe in all America (everyone can do Mister Rogers, but be forewarned: doing so is a sure sign of witlessness, even worse than doing Richard Nixon or Ed Sullivan). The voice creeps out adults, which is why everyone makes fun of it. But children are hypnotized by it. No adult ever spoke to them that way! Or at least no adult spoke that way without the condescension showing through. Mister Rogers could pull it off because Mister Rogers believed. (And didn't everyone call him Mister? Let's see the hands of children who address adults with honorifics nowadays.) If it was possible to be indifferent to Fred Rogers (and, yes, he could lull you to sleep), it was also impossible to muster even the faintest ill feeling. Adults may have found him a little off, and totally square, but his gentleness was never in question. We'll always cut Mister Rogers the slack we'll never grant to, say, "Barney." "I got into television because I hated it so," Rogers once said. "And I thought there's some way of using this fabulous instrument to nurture those who would watch and listen." Fred McFeely Rogers's evolution as a children's television personality began in the 1950s, many years before public TV station WQED in Pittsburgh produced the first "Neighborhood." Rogers had been a puppeteer and voice character (but never appeared on-screen) on a WQED show called "The Children's Corner." Indeed, in its twilight, "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" was a bridge to a long-forgotten television era, a one-set world of simple puppets, tooting trolleys, a handful of human characters (Lady Aberlin, Neighbor Aber, Mr. McFeely), a host and a jazz combo (Rogers himself wrote much of the show's music and played the piano). At some point in its long run, "Mister Rogers" went from black-and-white to color; you hardly noticed the difference. By the time of his last show, there was nothing else like it on TV. By then, "Romper Room" was a kinescopic memory, and so were "Kukla, Fran & Ollie" and "Captain Kangaroo." A thousand local kids' shows -- the regional "Wonderamas" and "Terry Tune Circuses" -- had been displaced by rackety animated fare whose principal mission was to deliver children to advertisers. And so, in a way, "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" looked both anachronistic and revolutionary. Rogers taught about empowerment, the power of love and self-acceptance, long before Oprah. Unlike Oprah, he did it on behalf of the defenseless and the innocent. That's the heart-rending aspect of "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood." You watch it as an adult and think about his simple message radiating out to a thousand, ten thousand, a million vulnerable little souls, some already so lost and bewildered. The beautiful thing about Fred Rogers was also the tragic thing: that he, a TV personality, was giving to children what many children never got from the adults around them. Sing it now, you'll feel better: It's such a good feeling to know you're alive. It's such a happy feeling: You're growing inside. And when you wake up ready to say, 'I think I'll make a snappy new day.' It's such a good feeling, a very good feeling. The feeling you know that I'll be back when the day is new And I'll have more ideas for you. And you'll have things you'll want to talk about. I will, too. And then? And then Koko took off Mister Rogers's shoes. Rogers' Family Communications Inc. changed its Web site to announce the death and to give advice on how to tell children about it. REV. FRED ROGERS 1928-2003

Like just about everybody else, I too, have my memories of Mister Rogers. He always came into his make believe house on the set, put on his tennis shoes and zip up cardigan sweater and went about sharing his time and always left us with a lesson we could share with others. For that was always his intent. An ordained Presbyterian minister, he knew the scriptural counsel that eloquently states "and a little child shall lead them." (Isaiah 11:6) - and lead the little children did as they brought their parents to the television sets to share Mister Rogers with their Moms and Dads. Always a good sport, Fred knew his television persona would be the butt of jokes, perhaps the best known of which was Eddie Murphy on Saturday Night Live doing a "Mister Robinson's Neighborhood" spoof that Fred found hilarious. I saw the same episode and found it laugh-out-loud funny myself. Back in 1986, while living in California and attending a Young Single Adult congregation, I was assigned the lesson for the Monday Family Home Evening. For those who aren't Latter-day Saints, we of the faith put aside Monday nights (or other night if there's a work or other fixed commitment) to be with our families. In this case, with a bunch of young singles, we use the night to be with each other for an evening of a fairly brief lesson, food and socializing. This was done at the Bishop's home, and given that my humor has a somewhat twisted side, I decided to take a run at "Mister Rollins' Neighborhood". When word got out that I was going to be 'creative' with the lesson, people who normally didn't show up for this decided to come. What they had absolutely no idea of was the approach I was going to take. Given that Mister Rogers was a childhood hero of sorts, I decided to both go easy on him, yet have some fun on this theme nonetheless. I assembled the props, zipper sweater, shoes and all. I even had Amy Hansen on the piano if memory serves and the lyrics down pat. She was the only one in on the gig. Poor Bishop Murray - he knew me well enough to expect the unexpected and that often scared him half to death. Anyway, the night of the lesson came, and it went off without a hitch. The lesson matter was approached in a simplistic "Mister Rogers" fashion in order to break the ice before going into the substance of it, and that led to a discussion the group had going for over an hour, followed by a humorous yet equally simplistic "Mister Rogers" fashion style of close before adjourning to having some food. That evening had a record turnout and had been one of the best evenings we had in the nearly two years I lived there. And so it was throughout his life with Fred Rogers. He taught throughout it - both on his television series and in his ministry, with his concert pianist wife Joanne, their two sons and two grandsons at his side. In humor and out, he even came out of retirement to instruct parents to help them better explain 9-11 to their children when replays of the attacks were shown on the one-year anniversary of that fateful day. Thinking of others throughout his life - such was the life and legacy of Fred Rogers. It reminds me of the first part of John 15:13, which states, "Greater love hath no man than this". Such a statement would be most appropriate as an epitaph for such a class act. Fred now goes on to his heavenly reward for a life well lived in service to the Master - a life so lived through service to his fellowmen, with a special focus on children, often overlooked and sometimes forgotten in the blind and vain ambitions of men. Take care, our kind and wonderful friend. May God tend you in His kind care and keeping until we meet again. |

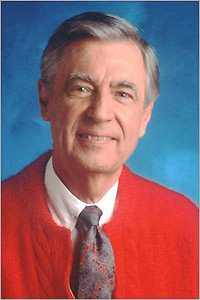

TV's Gentle Giant

TV's Gentle Giant  In a day and age where all

that's good seems to be drowned out by the crass and crude, along comes someone whose

message of good and simple caring for one another reaches across and inspires generations

of children and adults alike. And when that voice is silenced - for whatever reason, it

happens all too soon as it was with the passing of Fred Rogers (right) of "Mister

Rogers Neighborhood", who died Thursday of cancer at his Pittsburgh home at age 74.

In a day and age where all

that's good seems to be drowned out by the crass and crude, along comes someone whose

message of good and simple caring for one another reaches across and inspires generations

of children and adults alike. And when that voice is silenced - for whatever reason, it

happens all too soon as it was with the passing of Fred Rogers (right) of "Mister

Rogers Neighborhood", who died Thursday of cancer at his Pittsburgh home at age 74.