2005 MEATHEAD

AWARDS

Stupid Is As Stupid Does

by Judith

Haney,

The one and only judge in the contest!

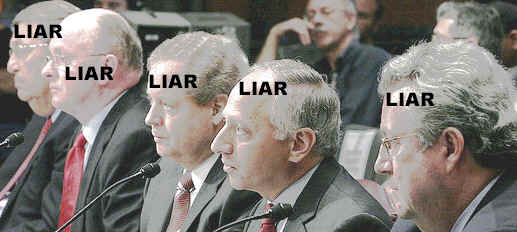

FIVE MEATHEADS

CAUGHT LYING TO CONGRESS

From left, MEATHEAD

Lee R. Raymond of Exxon Mobil, MEATHEAD David J. O'Reilly of Chevron, MEATHEAD James J. Mulva of ConocoPhillips, MEATHEAD Ross Pillari of BP

America and MEATHEAD John Hofmeister of Shell Oil.

Washington Post, Wednesday,

November 16, 2005

A White House document shows that executives from big oil companies met with Vice

President Cheney's energy task force in 2001 -- something long suspected by

environmentalists but denied as recently as last week by industry officials testifying

before Congress.

The document, obtained this week by The

Washington Post, shows that officials from Exxon Mobil Corp., Conoco (before its merger

with Phillips), Shell Oil Co. and BP America Inc. met in the White House complex with the

Cheney aides who were developing a national energy policy, parts of which became law and

parts of which are still being debated.

In a joint hearing last week of the Senate

Energy and Commerce committees, the chief executives of Exxon Mobil Corp., Chevron Corp.

and ConocoPhillips said their firms did not participate in the 2001 task force. The

president of Shell Oil said his company did not participate "to my knowledge,"

and the chief of BP America Inc. said he did not know.

Chevron was not named in the White House

document, but the Government Accountability Office has found that Chevron was one of

several companies that "gave detailed energy policy recommendations" to the task

force. In addition, Cheney had a separate meeting with John Browne, BP's chief executive,

according to a person familiar with the task force's work; that meeting is not noted in

the document.

The task force's activities attracted

complaints from environmentalists, who said they were shut out of the task force

discussions while corporate interests were present. The meetings were held in secret and

the White House refused to release a list of participants. The task force was made up

primarily of Cabinet-level officials. Judicial Watch and the Sierra Club unsuccessfully

sued to obtain the records.

Sen. Frank Lautenberg (D-N.J.), who posed

the question about the task force, said he will ask the Justice Department today to

investigate. "The White House went to great lengths to keep these meetings secret,

and now oil executives may be lying to Congress about their role in the Cheney task

force," Lautenberg said.

The executives were not under oath when

they testified, so they are not vulnerable to charges of perjury; committee Democrats had

protested the decision by Commerce Chairman Ted Stevens (R-Alaska) not to swear in the

executives. But a person can be fined or imprisoned for up to five years for making

"any materially false, fictitious or fraudulent statement or representation" to

Congress.

Alan Huffman, who was a Conoco manager

until the 2002 merger with Phillips, confirmed meeting with the task force staff. "We

met in the Executive Office Building, if I remember correctly," he said.

A spokesman for ConocoPhillips said the

chief executive, James J. Mulva, had been unaware that Conoco officials met with task

force staff when he testified at the hearing. The spokesman said that Mulva was chief

executive of Phillips in 2001 before the merger and that nobody from Phillips met with the

task force.

Exxon spokesman Russ Roberts said the

company stood by chief executive Lee R. Raymond's statement in the hearing. In a brief

phone interview, former Exxon vice president James Rouse, the official named in the White

House document, denied the meeting took place. "That must be inaccurate and I don't

have any comment beyond that," said Rouse, now retired.

Ronnie Chappell, a spokesman for BP,

declined to comment on the task force meetings. Darci Sinclair, a spokeswoman for Shell,

said she did not know whether Shell officials met with the task force, but they often meet

members of the administration. Chevron said its executives did not meet with the task

force but confirmed that it sent President Bush recommendations in a letter.

The person familiar with the task force's

work, who requested anonymity out of concern about retribution, said the document was

based on records kept by the Secret Service of people admitted to the White House complex.

This person said most meetings were with Andrew Lundquist, the task force's executive

director, and Cheney aide Karen Y. Knutson.

According to the White House document,

Rouse met with task force staff members on Feb. 14, 2001. On March 21, they met with

Archie Dunham, who was chairman of Conoco. On April 12, according to the document, task

force staff members met with Conoco official Huffman and two officials from the U.S. Oil

and Gas Association, Wayne Gibbens and Alby Modiano.

On April 17, task force staff members met

with Royal Dutch/Shell Group's chairman, Sir Mark Moody-Stuart, Shell Oil chairman Steven

Miller and two others. On March 22, staff members met with BP regional president Bob

Malone, chief economist Peter Davies and company employees Graham Barr and Deb Beaubien.

Toward the end of the hearing, Lautenberg

asked the five executives: "Did your company or any representatives of your companies

participate in Vice President Cheney's energy task force in 2001?" When there was no

response, Lautenberg added: "The meeting . . . "

"No," said Raymond.

"No," said Chevron Chairman

David J. O'Reilly.

"We did not, no," Mulva said.

"To be honest, I don't know,"

said BP America chief executive Ross Pillari, who came to the job in August 2001. "I

wasn't here then."

"But your company was here,"

Lautenberg replied.

"Yes," Pillari said.

Shell Oil president John Hofmeister, who

has held his job since earlier this year, answered last. "Not to my knowledge,"

he said.

MEATHEAD Bob "When

the story comes out, I'm quite confident we're going to find out that it started kind of

as gossip, as chatter"

Woodward has been discovered hiding the fact that a senior Bush

administration official told him about CIA agent Valerie Plame more than two years before

the indictment of Lewis LIbby - all the while Woodward has been appearing on television

and giving interviews minimizing and degrading the special prosecutor's investigation. MEATHEAD Bob "When

the story comes out, I'm quite confident we're going to find out that it started kind of

as gossip, as chatter"

Woodward has been discovered hiding the fact that a senior Bush

administration official told him about CIA agent Valerie Plame more than two years before

the indictment of Lewis LIbby - all the while Woodward has been appearing on television

and giving interviews minimizing and degrading the special prosecutor's investigation.

Washington Post Assistant Managing Editor

Bob Woodward testified under oath Monday, November 14, 2005, in the CIA leak case that a

senior administration official told him about CIA operative Valerie Plame and her position

at the agency nearly a month before her identity was disclosed.

In a more than two-hour deposition,

Woodward told Special Counsel Patrick J. Fitzgerald that the official casually told him in

mid-June 2003 that Plame worked as a CIA analyst on weapons of mass destruction, and that

he did not believe the information to be classified or sensitive, according to a statement Woodward released yesterday.

Fitzgerald interviewed Woodward about the

previously undisclosed conversation after the official alerted the prosecutor to it on

Nov. 3 -- one week after Vice President Cheney's chief of staff, I. Lewis

"Scooter" Libby, was indicted in the investigation.

Citing a confidentiality agreement in

which the source freed Woodward to testify but would not allow him to discuss their

conversations publicly, Woodward and Post editors refused to disclose the official's name

or provide crucial details about the testimony. Woodward did not share the information

with Washington Post Executive Editor Leonard Downie Jr. until last month, and the only

Post reporter whom Woodward said he remembers telling in the summer of 2003 does not

recall the conversation taking place.

Woodward said he also testified that he

met with Libby on June 27, 2003, and discussed Iraq policy as part of his research for a

book on President Bush's march to war. He said he does not believe Libby said anything

about Plame.

He also told Fitzgerald that it is

possible he asked Libby about Plame or her husband, former ambassador Joseph C. Wilson IV.

He based that testimony on an 18-page list of questions he planned to ask Libby in an

interview that included the phrases "yellowcake" and "Joe Wilson's

wife." Woodward said in his statement, however, that "I had no

recollection" of mentioning the pair to Libby. He also said that his original

government source did not mention Plame by name, referring to her only as "Wilson's

wife."

Woodward's testimony appears to change key

elements in the chronology Fitzgerald laid out in his investigation and announced when

indicting Libby three weeks ago. It would make the unnamed official -- not Libby -- the

first government employee to disclose Plame's CIA employment to a reporter. It would also

make Woodward, who has been publicly critical of the investigation, the first reporter

known to have learned about Plame from a government source.

The testimony, however, does not appear to

shed new light on whether Libby is guilty of lying and obstructing justice in the nearly

two-year-old probe or provide new insight into the role of senior Bush adviser Karl Rove,

who remains under investigation.

Mark Corallo, a spokesman for Rove, said

that Rove is not the unnamed official who told Woodward about Plame and that he did not

discuss Plame with Woodward.

William Jeffress Jr., one of Libby's

lawyers, said yesterday that Woodward's testimony undermines Fitzgerald's public claims

about his client and raises questions about what else the prosecutor may not know. Libby

has said he learned Plame's identity from NBC's Tim Russert.

"If what Woodward says is so, will

Mr. Fitzgerald now say he was wrong to say on TV that Scooter Libby was the first official

to give this information to a reporter?" Jeffress said last night. "The second

question I would have is: Why did Mr. Fitzgerald indict Mr. Libby before fully

investigating what other reporters knew about Wilson's wife?"

Fitzgerald has spent nearly two years

investigating whether senior Bush administration officials illegally leaked classified

information -- Plame's identity as a CIA operative -- to reporters to discredit

allegations made by Wilson. Plame's name was revealed in a July 14, 2003, column by Robert

D. Novak, eight days after Wilson publicly accused the administration of twisting

intelligence to justify the Iraq war. Fitzgerald's spokesman, Randall Samborn, declined to

comment yesterday.

Woodward is a Pulitzer Prize-winning

investigative reporter and author best known for exposing the Watergate scandal and

keeping secret for 30 years the identity of his government source "Deep Throat."

"It was the first time in 35 years as

a reporter that I have been asked to provide information to a grand jury," he said in

the statement.

Downie said The Post waited until late

yesterday to disclose Woodward's deposition in the case in hopes of persuading his sources

to allow him to speak publicly. Woodward declined to elaborate on the statement he

released to The Post late yesterday afternoon and publicly last night. He would not answer

any questions, including those not governed by his confidentiality agreement with sources.

According to his statement, Woodward also testified about a third unnamed source. He told

Fitzgerald that he does not recall discussing Plame with this person when they spoke on

June 20, 2003.

It is unclear what prompted Woodward's

original unnamed source to alert Fitzgerald to the mid-June 2003 mention of Plame to

Woodward. Once he did, Fitzgerald sought Woodward's testimony, and three officials

released him to testify about conversations he had with them. Downie, Woodward and a Post

lawyer declined to discuss why the official may have stepped forward this month.

Downie defended the newspaper's decision

not to release certain details about what triggered Woodward's deposition because "we

can't do anything in any way to unravel the confidentiality agreements our reporters

make."

Woodward never mentioned this contact --

which was at the center of a criminal investigation and a high-stakes First Amendment

legal battle between the prosecutor and two news organizations -- to his supervisors until

last month. Downie said in an interview yesterday that Woodward told him about the contact

to alert him to a possible story. He declined to say whether he was upset that Woodward

withheld the information from him.

Downie said he could not explain why

Woodward said he provided a tip about Wilson's wife to Walter Pincus, a Post reporter

writing about the subject, but did not pursue the matter when the CIA leak investigation

began. He said Woodward has often worked under ground rules while doing research for his

books that prevent him from naming sources or even using the information they provide

until much later.

Woodward's statement said he testified:

"I told Walter Pincus, a reporter at The Post, without naming my source, that I

understood Wilson's wife worked at the CIA as a WMD analyst."

Pincus said he does not recall Woodward

telling him that. In an interview, Pincus said he cannot imagine he would have forgotten

such a conversation around the same time he was writing about Wilson.

"Are you kidding?" Pincus said.

"I certainly would have remembered that."

Pincus said Woodward may be confused about

the timing and the exact nature of the conversation. He said he remembers Woodward making

a vague mention to him in October 2003. That month, Pincus had written a story explaining

how an administration source had contacted him about Wilson. He recalled Woodward telling

him that Pincus was not the only person who had been contacted.

Pincus and fellow Post reporter Glenn

Kessler have been questioned in the investigation.

Woodward, who is preparing a third book on

the Bush administration, has called Fitzgerald "a junkyard-dog prosecutor" who

turns over every rock looking for evidence. The night before Fitzgerald announced Libby's

indictment, Woodward said he did not see evidence of criminal intent or of a major crime

behind the leak.

"When the story comes out, I'm quite

confident we're going to find out that it started kind of as gossip, as chatter," he

told CNN's Larry King.

Woodward also said in interviews this

summer and fall that the damage done by Plame's name being revealed in the media was

"quite minimal."

"When I think all of the facts come

out in this case, it's going to be laughable because the consequences are not that

great," he told National Public Radio this summer.

On November 17, 2005, Bob Woodward

apologized to The Washington Post yesterday for failing to reveal for more than two years

that a senior Bush administration official had told him about CIA operative Valerie Plame,

even as an investigation of who disclosed her identity mushroomed into a national scandal.

Woodward, an assistant managing editor and

best-selling author, said he told Executive Editor Leonard Downie Jr. that he held back

the information because he was worried about being subpoenaed by Patrick J. Fitzgerald,

the special counsel leading the investigation.

"I apologized because I should have

told him about this much sooner," Woodward, who testified in the CIA leak

investigation Monday, said in an interview. "I explained in detail that I was trying

to protect my sources. That's job number one in a case like this. . . .

"I hunkered down. I'm in the habit of

keeping secrets. I didn't want anything out there that was going to get me

subpoenaed."

Downie, who was informed by Woodward late

last month, said his most famous employee had "made a mistake." Despite

Woodward's concerns about his confidential sources, Downie said, "he still should

have come forward, which he now admits. We should have had that conversation. . . . I'm

concerned that people will get a mis-impression about Bob's value to the newspaper and our

readers because of this one instance in which he should have told us sooner."

The belated revelation that Woodward has

been sitting on information about the Plame controversy reignited questions about his

unique relationship with The Post while he writes books with unparalleled access to

high-level officials, and about why Woodward denigrated the Fitzgerald probe in television

and radio interviews while not divulging his own involvement in the matter.

"It just looks really bad," said

Eric Boehlert, a Rolling Stone contributing editor and author of a forthcoming book on the

administration and the press. "It looks like what people have been saying about Bob

Woodward for the past five years, that he's become a stenographer for the Bush White

House."

Said New York University journalism

professor Jay Rosen: "Bob Woodward has gone wholly into access journalism."

Robert Zelnick, chairman of Boston

University's journalism department, said: "It was incumbent upon a journalist, even

one of Woodward's stature, to inform his editors. . . . Bob is justifiably an icon of our

profession -- he has earned that many times over -- but in this case his judgment was

erroneous."

Shortly after Woodward's conversation with

Downie in late October, a federal grand jury indicted Vice President Cheney's chief of

staff, I. Lewis "Scooter" Libby, on charges of perjury and obstruction of

justice in the Plame case. Woodward told Fitzgerald that he met with Libby on June 27,

2003, but that he does not recall discussing Plame or her husband, White House critic and

former ambassador Joseph C. Wilson IV.

Yesterday, White House Chief of Staff

Andrew H. Card Jr. said that he was a source whom Woodward testified he spoke with during

that period. But Woodward said that neither Plame nor Wilson came up during that

conversation.

Fitzgerald has spent nearly two years

investigating whether administration officials illegally leaked Plame's name to the media

to discredit Wilson.

Exactly what triggered Woodward's

disclosure to Downie remains unclear. Woodward said yesterday that he was "quite

aggressively reporting" a story related to the Plame case when he told Downie about

his involvement as the term of Fitzgerald's grand jury was set to expire on Oct. 28.

The administration source who originally

told Woodward about Plame approached the prosecutor recently to alert him to his 2003

conversation with Woodward. The source had not yet contacted Fitzgerald when Woodward

notified Downie about their conversation, Woodward said.

"After Libby was indicted, [Woodward]

noticed how his conversation with the source preceded the timing in the indictment,"

Downie said yesterday. "He's been working on reporting around that subject ever since

the indictment."

Once Fitzgerald contacted Woodward on Nov.

3 with a request to testify, the newspaper's lawyers asked that nothing be published until

after the deposition, Woodward said.

The disclosure has prompted critics to

compare Woodward to Judith Miller, a New York Times reporter who left the newspaper last

week amid questions about her lone-ranger style and why she had not told her editors

sooner about her involvement in the Plame matter. An online posting at Reason magazine

called Woodward "Mr. Run Amok," a play on Miller's nickname at the Times.

Neither reporter wrote a story on the subject.

Rem Rieder, editor of American Journalism

Review, called Woodward's disclosure "stunning" and said it "seems awfully

reminiscent of what we criticized Judith Miller for."

Times Executive Editor Bill Keller accused

Miller of misleading the paper by not disclosing earlier that she had discussed Plame with

Libby. Managing Editor Jill Abramson has said she has no recollection of Miller suggesting

that she pursue a story on the Plame matter, as Miller has maintained.

In Woodward's case, he says he passed

along a tip about Plame to Post reporter Walter Pincus in June 2003, but Pincus says he

has no recollection of such a conversation. Pincus has also testified in the probe but,

like Woodward, has not obtained permission from one source to disclose that person's

identity.

Woodward has criticized the Fitzgerald

probe in media appearances. He said on MSNBC's "Hardball" in June that in the

end "there is going to be nothing to it. And it is a shame. And the special

prosecutor in that case, his behavior, in my view, has been disgraceful." In a

National Public Radio interview in July, Woodward said that Fitzgerald made "a big

mistake" in going after Miller and that "there is not the kind of compelling

evidence that there was some crime involved here."

Rieder said it was "kind of

disingenuous" for Woodward to have made such comments without disclosing his

involvement.

Liberal blogger Josh Marshall wrote:

"By becoming a partisan in the context of the leak case without revealing that he was

at the center of it, really a party to it, he wasn't being honest with his audience."

Downie said Woodward had violated the

newspaper's guidelines in some instances by expressing his "personal views."

During the Watergate scandal, Woodward

protected the identity of "Deep Throat" -- the government source who helped

reveal Nixon administration corruption -- and kept the secret until former FBI official W.

Mark Felt went public this spring. In this case, Woodward is protecting a Bush

administration official who may be part of an effort to strike back at a White House

critic. Woodward said he has "pushed" his source, without success, for

permission to discuss the matter publicly.

Woodward and Downie said they doubt that

The Post could have found a way to publish the content of Woodward's conversation, which

under the ground rules established with the source was off the record. Woodward said that

the unnamed official told him about Plame "in an offhand, casual manner . . . almost

gossip" and that "I didn't attach any great significance to it."

Woodward said he realized that his June

2003 conversation with the unnamed official had greater significance after Libby was

described in an indictment as having been the first administration official to tell a

reporter -- the Times' Miller -- about Plame. Downie said he has told Woodward that he

must be more communicative about sensitive matters in the future.

Woodward said that it was "pretty

frightening" to watch Fitzgerald threatening reporters with jail -- Miller served 85

days for initially refusing to testify -- and that he "had a lot of pent-up

frustration." Woodward said that he "was trying to get the information out and

couldn't" because of his agreement with his source.

Woodward has periodically faced criticism

for holding back scoops for his Simon & Schuster-published books, which are invariably

trumpeted by The Post, and several Post staff members complained yesterday in in-house

critiques of the newspaper about his role.

Downie said he remains comfortable with

the arrangement, under which Woodward spends most of his time researching his books, such

as "Bush at War" and "Plan of Attack," while giving The Post the first

excerpts and occasionally writing news stories. He said Woodward "has brought this

newspaper many important stories he could not have gotten without these book

projects."

Woodward, who had lengthy interviews with

President Bush for his two most recent books, dismissed criticism that he has grown too

close to White House officials. He said he prods them into providing a fuller picture of

the administration's inner workings.

"The net to readers is a voluminous

amount of quality, balanced information that explains the hardest target in

Washington," Woodward said, referring to the Bush administration.

EDITOR'S

NOTE: The following is Woodward's statement released in the Washington Post on Wednesday,

November 15, 2005

"On Monday, November 14, I testified

under oath in a sworn deposition to Special Counsel Patrick J. Fitzgerald for more than

two hours about small portions of interviews I conducted with three current or former Bush

administration officials that relate to the investigation of the public disclosure of the

identity of undercover CIA officer Valerie Plame.

The interviews were mostly confidential

background interviews for my 2004 book "Plan of Attack" about the leadup to the

Iraq war, ongoing reporting for The Washington Post and research for a book on Bush's

second term to be published in 2006. The testimony was given under an agreement with

Fitzgerald that he would only ask about specific matters directly relating to his

investigation.

All three persons provided written

statements waiving the previous agreements of confidentiality on the issues being

investigated by Fitzgerald. Each confirmed those releases verbally this month, and

requested that I testify.

Plame is the wife of former ambassador

Joseph Wilson, who had been sent by the CIA in February 2002 to Niger to determine if

there was any substance to intelligence reports that Niger had made a deal to sell

"yellowcake" or raw uranium to Iraq. Wilson later emerged as an outspoken critic

of the Bush administration.

I was first contacted by Fitzgerald's

office on Nov. 3 after one of these officials went to Fitzgerald to discuss an interview

with me in mid-June 2003 during which the person told me Wilson's wife worked for the CIA

on weapons of mass destruction as a WMD analyst.

I have not been released to disclose the

source's name publicly.

Fitzgerald asked for my impression about

the context in which Mrs. Wilson was mentioned. I testified that the reference seemed to

me to be casual and offhand, and that it did not appear to me to be either classified or

sensitive. I testified that according to my understanding an analyst in the CIA is not

normally an undercover position.

I testified that after the mid-June 2003

interview, I told Walter Pincus, a reporter at The Post, without naming my source, that I

understood Wilson's wife worked at the CIA as a WMD analyst. Pincus does not recall that I

passed this information on.

Fitzgerald asked if I had discussed

Wilson's wife with any other government officials before Robert Novak's column on July 14,

2003. I testified that I had no recollection of doing so.

He asked if I had possibly planned to ask

questions about what I had learned about Wilson's wife with any other government official.

I testified that on June 20, 2003, I

interviewed a second administration official for my book "Plan of Attack" and

that one of the lists of questions I believe I brought to the interview included on a

single line the phrase "Joe Wilson's wife." I testified that I have no

recollection of asking about her, and that the tape-recorded interview contains no

indication that the subject arose.

I also testified that I had a conversation

with a third person on June 23, 2003. The person was I. Lewis "Scooter" Libby,

and we talked on the phone. I told him I was sending to him an 18-page list of questions I

wanted to ask Vice President Cheney. On page 5 of that list there was a question about

"yellowcake" and the October 2002 National Intelligence Estimate regarding

Iraq's weapons programs. I testified that I believed I had both the 18-page question list

and the question list from the June 20 interview with the phrase "Joe Wilson's

wife" on my desk during this discussion. I testified that I have no recollection that

Wilson or his wife was discussed, and I have no notes of the conversation.

Though neither Wilson nor Wilson's wife's

name had surfaced publicly at this point, Pincus had published a story the day before,

Sunday, June 22, about the Iraq intelligence before the war. I testified that I had read

the story, which referred to the CIA mission by "a former senior American diplomat to

visit Niger." Although his name was not used in the story, I knew that referred to

Wilson.

I testified that on June 27, 2003, I met

with Libby at 5:10 p.m. in his office adjacent to the White House. I took the 18-page list

of questions with the Page-5 reference to "yellowcake" to this interview and I

believe I also had the other question list from June 20, which had the "Joe Wilson's

wife" reference.

I have four pages of typed notes from this

interview, and I testified that there is no reference in them to Wilson or his wife. A

portion of the typed notes shows that Libby discussed the October 2002 National

Intelligence Estimate on Iraq's alleged weapons of mass destruction, mentioned

"yellowcake" and said there was an "effort by the Iraqis to get it from

Africa. It goes back to February '02." This was the time of Wilson's trip to Niger.

When asked by Fitzgerald if it was

possible I told Libby I knew Wilson's wife worked for the CIA and was involved in his

assignment, I testified that it was possible I asked a question about Wilson or his wife,

but that I had no recollection of doing so. My notes do not include all the questions I

asked, but I testified that if Libby had said anything on the subject, I would have

recorded it in my notes.

My testimony was given in a sworn

deposition at the law office of Howard Shapiro of the firm of Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale

and Dorr instead of appearing under subpoena before a grand jury.

I testified after consulting with the

Post's executive and managing editors, the publisher, and our lawyers. We determined that

I could testify based on the specific releases obtained from these three people. I

answered all of Fitzgerald's questions during my testimony without breaking promises to

sources or infringing on conversations I had on unrelated matters for books or news

reporting -- past, present or future.

It was the first time in 35 years as a

reporter that I have been asked to provide information to a grand jury."

Meathead Oprah "You can take the girl

out of the slums, but you can't take the slums out of the GIRLLL " Winfrey, has gotten on our last nerve with

her ridiculous accusations of racial bias against Hermes, the store in Paris whose doors

had closed fifteen minutes BEFORE Miss Priss and the Prissettes showed up demanding to be

let in.

She

wasn’t let in. National emergency! What’s the deal? She was too late. Hermes is

quite possibly one of the most expensive clothing and bag makers in the entire world. Not

being let into Hermes was supposedly Oprah’s “Crash Moment.”

Since when

does an over-blown, self-centered, ego like Oprah need to BORE the rest of us with her

trashy fits of rage over a retail store failing to kiss her backside? And what business is

it of Oprah's that Hermes was in the midst of preparing for a private store function when

she showed up unannounced AFTER the store had closed for the day?

I'm not sympathetic to ANY

celebrity - black or white - who is misguided enough to believe that they have a right to

do what the rest of us can't and then abuse their celebrity status by waging an

unwarranted smear campaign.

Based upon Oprah's

current obnoxious behavior it is obvious that she is much more concerned with looking

classy, than ACTING classy. Oprah, your Hermes conduct begs the question - is this the way

you behaved BEFORE THE MONEY? - JUDITH HANEY

2006

Meatheads

2005

Meatheads

2004

Meatheads

2003

Meatheads

2002

Meatheads |

MEATHEAD Bob "When

the story comes out, I'm quite confident we're going to find out that it started kind of

as gossip, as chatter"

Woodward has been discovered hiding the fact that a senior Bush

administration official told him about CIA agent Valerie Plame more than two years before

the indictment of Lewis LIbby - all the while Woodward has been appearing on television

and giving interviews minimizing and degrading the special prosecutor's investigation.

MEATHEAD Bob "When

the story comes out, I'm quite confident we're going to find out that it started kind of

as gossip, as chatter"

Woodward has been discovered hiding the fact that a senior Bush

administration official told him about CIA agent Valerie Plame more than two years before

the indictment of Lewis LIbby - all the while Woodward has been appearing on television

and giving interviews minimizing and degrading the special prosecutor's investigation.